Ron Gregg, Senior Lecturer in Film at Columbia University, sat down with Bryson Rand to talk about the most recent developments in Rand's photographic practice. They dig into crucial aspects related to the construction of the image, such as the documentary nature of photography, the use of black and white, the relationship between the model and the photographer, and the pursuit of beauty. The conversation also led to an exploration of the connection between bodies and nature in Rand's work, revealing a common barbarism endured by LGTBQ communities and the planet.

I first met you at Yale and I remember your work at that time was mostly of male bodies. There were some nature photos, all black and white. You were defining yourself, but most of your faculty were struggling to figure out what you were doing. You said that you were still kind of discovering yourself, so on some level Yale did work in pushing you or throwing you into the lake.

Yeah, I think that while I was at Yale, was the first time I was really able to declare myself an artist without any sort of doubt. Before then, I defined myself as a teacher who made photographs or something. So yeah, at that time it really felt important to go hard into things. My work prior to grad school had really been skirting around my sexuality. I was photographing other gay men, but in this very kind of generic sense. I had this approach of "I'll just document things and not really intervene." That changed when I was in school and was faced with confusion or resistance on the part of the panel and the critics there. Looking back now, it was very beneficial that they gave me something to push back against.

I remember the first time you and I met, I was really struggling to find useful feedback that wasn't just about the photographic nature of the work. I was interested in history. I was interested in grieving this history, in finding my own place within all this loss in the generations prior to mine. I remember you came into the studio and I felt like you just understood the references I was working with, the history that I was engaged in. In so many of my previous studio visits, I had to start from the bottom and be like: here's a history of all these things, and you just sort of came in and it felt like you knew what I was engaged with already, which was really incredible and helpful.

Illuminated Ice (Fellsfjara, Iceland), 2019

When you talk about the shift in your work, were you mostly making 'candid' portraits of male bodies and then all of a sudden there was this kind of energy that you brought in and enacted in the work? I love that you use the word document. You know, that you were documenting these bodies, these lives, their sex, but there was a sense in the images I saw of participation. I felt like I was not just voyeuristically observing, but that your camera was in the action on some level. There was a profound shift that you made at that point.

Absolutely. In my last semester of school my computer crashed. I think I lost a lot of work that I had been making prior to school, which sucks, but is also sort of like, "well whatever." The way that I was operating prior to grad school, was to go to parties, or be at a friend's house, or photographing in bars and trying this fly on the wall type of photography, which I think is something that's kind of ingrained into a lot of photo history, especially US centered photographic practice. It's all about Garry Winogrand or Lee Friedlander and you're out there capturing things happening in front of you, but your intervention really just happens through the camera. How you are depicting the thing rather than actually injecting yourself in the situation, calling the shots, influencing it. Prior to school, I had done a little bit of setting up photo shoots with guys and going to their apartment. I started making some very timid nudes but I felt really uncomfortable being a director in that sense, because of a lot of the teaching I'd had.

When I was in school, there was one critique where I was criticized for not having a gay aesthetic and someone assumed that I didn't know about the AIDS crisis in the '80s, which was incredibly offensive and made me very mad. And then after that, that was my first semester, I kind of really dug into researching literature, movies, anything I could find centered on the history of gay male culture in the U.S. with a really intense focus on the '80s and '90s, which was the peak of the AIDS crisis. I started to realize more and more it was something that deeply affected me and my generation and how I dealt with my desires, my sexuality. I wanted to figure out a way to infuse the work with all this new knowledge or even the grief that I was feeling, which would also come up in conversations with the people that I was photographing who were sometimes friends, sometimes strangers. As these things would come up I began looking for a way to channel that energy, or that history, and use the work to bring that presence into some sort of visual form. I realized that just standing back and documenting things wasn't going to do that for me. I really had to direct things through lighting, through the action, and as I got more and more confident in that I got more excited about the potential in that way of working to make new types of photographs.

Mist (Dettifoss, Iceland), 2019

That's so helpful because so many of the gay photographers in the 80s and 90s were documenting the community. They were very much involved. It also explains something to me, one of the questions I was going to ask: why black and white? Also, much of that photography captured a kind of more natural body and not in idealized body, and even bodies as they became sicker. They were still documenting a kind of movement, you know of their health but their bodies themselves, sort of naked and showing the effect of the disease, of HIV upon them and they wanted to document that. That really answers one of the questions I had about your choice of bodies and the way that you light them and how using black and white brings it out of using the kind of Mapplethorpe beauty and perfection, into something that is more about that kind of gritty Lower East Side in the 80s and 90s, kind of community. I'm also thinking of Mark Morrisroe and people like that.

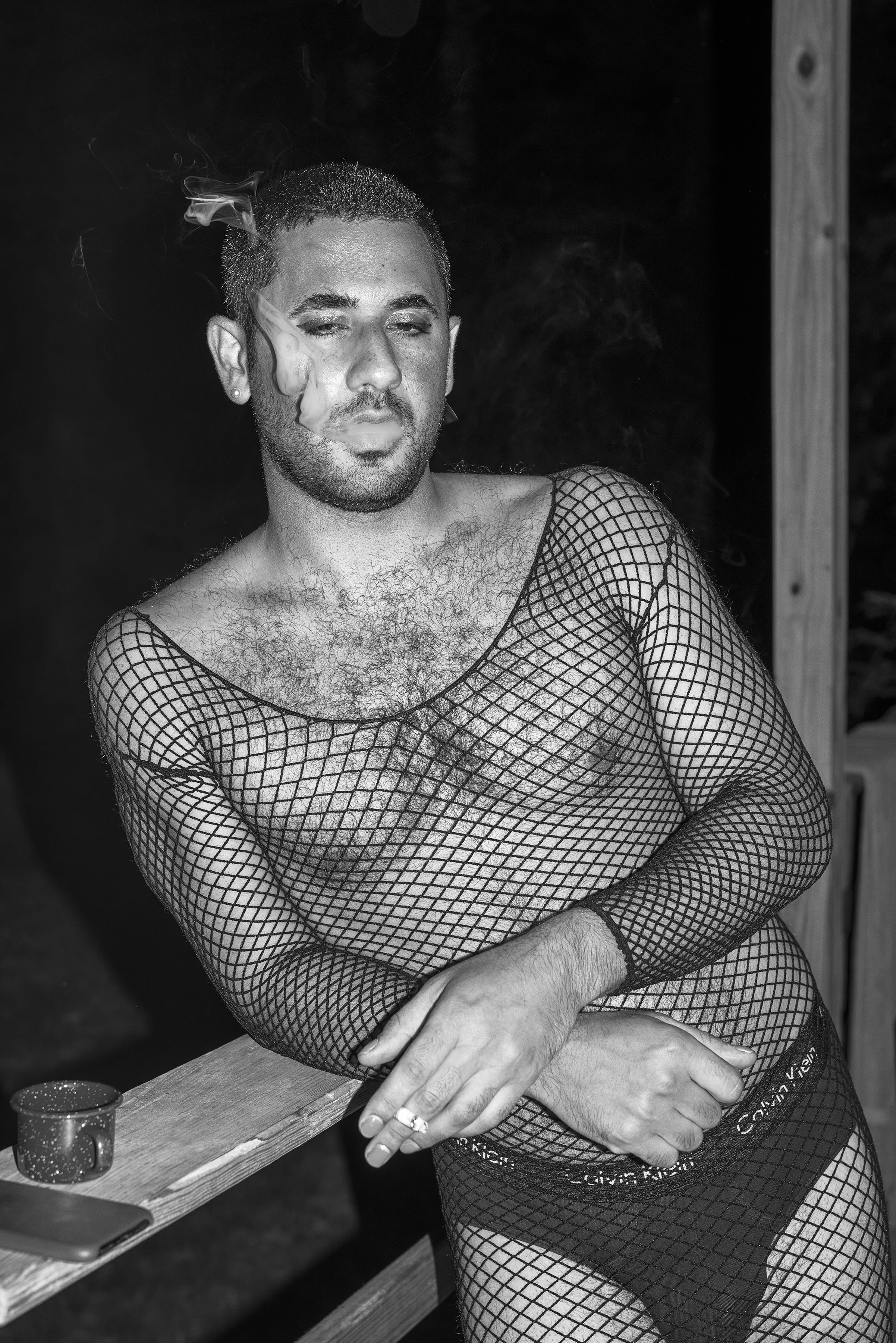

Well, full disclosure, I'm really bad at making color photographs and I sort of stopped doing that before grad school. I was applying to school and a friend was looking through my work which was in color at the time. He said, "You know, you're pictures are in color, but the color is not really doing anything. They're just in color." I thought, "You're kind of right," and I started experimenting in black and white again. I just found that with the removal of color, I could see things better, I could construct a more exciting frame. It became more about texture and shape. I really love photographing skin and hair in black and white. There is something so beautiful about that. And then as the work was developing and I was finding my voice, I did love the fact that black and white puts the work into a nondescript time period. It could be 2013, 2019, or 1970. I was also interested in, as much as humanly possible, not having signs of the current moment. I don't like to have technology in the photographs. Obviously hairstyles, tattoos, or that kind of stuff will give you some sense of time. But I did feel that working in black and white I could communicate between these different time periods and move more fluidly through them. You bring up something I think about a lot. This sort of idea, you know Peter Hujar, Mark Morrisroe, Nan Goldin, that these people were in various ways documenting a community that was under threat and then was rapidly disappearing as time went on. This is a question I still think about: what does it mean to continue that tradition or maybe pick up where things were dropped?

I don't necessarily mean document in the sense of documentary photography, but more as some sort of proof. I listened to this Nan Goldin lecture while I was at Skowhegan this summer, and she talks about her work being proof of a history that can't be denied or interfered with. I'd always had a little bit of a problem with some of the ways her work is talked about as being like 'this is the most accurate, truthful depiction of my life and my community's life'. But I think the idea of it being some sort of proof, even though it might not be "the truth," it's still undeniable proof that we existed, we did these things. In her best work you can really see the engagement, the friendships, the pain, the joy, and that is something that I think about in my own work a lot.

Jack at the Sink (Skowhegan), 2019

You talked about the types of bodies that I photograph, and Mapplethorpe has never been my favorite. I find his work to be rather cold. I think that’s partially just how things are photographed, but it also goes back to these perfect, beautiful, sculptural bodies. That’s not really what I’m attracted to and I find there’s something so much more interesting in seeing the hair and the scars and rolls. That’s what I’m more attracted to. There’s something more visceral in seeing a body that doesn’t take you right into this fantasy and away from the humanity of it.

Are most of the models, if I can use this word, people that you know? Do you ever hire models? How does that work for you now?

I've never paid anyone to pose. In grad school, it was mostly strangers. It was actually a combination between strangers and people that I knew or people that I was acquainted with. It's a process of seeking people out. There are certain people I approach who I'd love to photograph for whatever reason, either because I'm just physically attracted them or I'm just drawn to their personality. Sometimes it's like: "You have really cool tattoos. Can I photograph you?"

For a while, it was easier for me to photograph people I wasn't as close to. I still can't really make good pictures of my husband, Ryan. Or at least I have made very few good pictures of him. Part of it is because he is a little bit disagreeable when I photograph him. He doesn't tolerate as much as other people I photograph do. A lot of the work of making photographs is repetition of movements or me moving around while they are holding a pose. Most people are pretty obliging and Ryan will be like "I'm done. We're done. We did it," and he'll put his shirt back on and like stomp out of the room. I found that if I flatter him "ooh, babe, you look really great in this light" he will kind of indulge me a little bit more.

I think part of it is sort of the excitement of getting to know someone in that moment. Jimmy, for instance, is someone that I don't know super well, we're not super close friends. Typically in our interactions he's pretty quiet and little bit shy, but when he came into the studio recently, he was fired up and his excitement got me excited.

Jeffrey (Skowhegan), 2019

There is one thing going back to grad school, and even today there's always this question of "what gives you the right to make these photos?." There is always this tension around whether your work is exploiting people. Is this morally right? I think that argument or that dismissal can be very frustrating because people, as much as I seek people out, sometimes come to me and say "oh I like your work" or "I'd love to be photographed by you" or whatever. So, I have my intentions and desires and the people I photograph have their intentions and desires. I really try to make it a situation where they're getting something out of it. Whether it's just indulging in a fantasy or there's something about being looked at or you know, not to toot my own horn, but a lot of times people will say "Oh, wow! I've never seen myself in this way." Some people say "I'm self-conscious about my body and you alleviated me of that while we were shooting," and I do think that's important. I want people to feel comfortable and respected and that it's a mutual exchange of some sort. Photographing someone I don't know very well is similar to entering into a new landscape that I'm unfamiliar with. It's visually and mentally exciting. I see things, I respond to things. I'm so intimately knowledgeable of Ryan and his body that sometimes I think that can be a little bit of a mental block, like how do I photograph him in a way that's going to be exciting to me that will be conveyed through the photograph?

Actually, lately I've been trying to work more with people who I consider to be close friends, or lovers, or just people that I'm more intimately involved with. That doesn't mean that I won't photograph a stranger or an acquaintance, but it has been sort of a shift in what my intention is. I think because that has been a mental block, it's just something I need to conquer.

So this is a nice segue because you mentioned that bodies can be like landscapes. So you document landscapes, nature. Is there an energy and excitement that is different than that sense of how desire plays out in documenting a body? What would be the language that you use to describe what inspires you as you look at some of the nature shots like this one right here (Untitled/Lake Water (Skowhegan))? You've photographed the light and the water, these textures, making it beautiful, kind of complicated. It's not just textures but a kind of landscape, and the spaces that you're choosing have a sort of movement or complexity to them along with the light and the textures.

Untitled/Lake Water (Skowhegan), 2019

Yeah. Going back to my early education in photography, I loved Robert Frank. The Americans was the first photo book I got, and the idea of capturing the mundane or capturing something that you were just surrounded by all the time and making it into something photographically exciting really informed my work for a long time.

Going back to grad school, when I started I was working in a way that was trying to be like a street photographer because I just thought that's what you did. Then as I started to shift into these more intimate, indoor, kind of private encounters, it didn't feel like it was enough to just show bodies in these interior spaces. I wanted there to be a connection to the larger world. I started photographing very dense vegetation when I was in Okinawa visiting my sister, and then I was in Los Angeles kind of doing the same thing. Just finding that I was really excited by the light, the succulents, the palm trees, and how the light was interacting with them. It became sort of a clue to how those two modes of making photographs could fuse together. I started to figure out the kind of formal connections between the external world and the way I was photographing bodies.

At that time, I was really thinking of the landscapes as representing this sort of psychological shift. There were these very dense walls of plant life, and I imagined if you're moving through the photos, these are obstacles you have to move around or through. They sort of countered the freedom of expression of desire and sexuality in the pictures of bodies, with this other more blocked psychological state that I think a lot of gay men and queer people have to overcome because we deal with all the shit from society and all the traumas, and stress, and shame. In my more recent work it's a similar thing. I think that there is an interesting shift in psychology when you're looking at a body or portrait and then you're looking at a landscape. But I want there to be some sort of connection. I think the light, the textures, and even the fact that the photographs are shot in a portrait orientation, formally ties them together.

I had a studio visit with Shirin Neshat in school, and she talked about the way she was interpreting the pairing of the bodies and the landscape. Saying, the idea of introducing nature makes a statement that these physical acts are natural. These desires are natural. There's nothing wrong or shameful about them, which is a counterbalance to what I was taught growing up. This is something that has been coming up in conversations about the more recent work too.

I think that this is some of the language I was trying to draw upon at Yale when I first saw the nature along with the bodies. On some level the erections and cum, can look dirty, but then if you put it in a kind of space of nature all of a sudden it is part of nature. It is natural, even though we've created these kind of taboos about something that really is part of our process, part of our natural being: you piss, you shit, you cum. You can't avoid it! It's there! But you are supposed to shut the door and hide from it. So, I would agree. The person that I always thought did that beautifully in the '70s was Barbara Hammer. You have this radical lesbian separatist community, but she would film them out in nature and it's like their love, their bodies all of a sudden became natural. Even though their bodies weren't classically beautiful, all of a sudden they became natural. This is beautiful. It should be beautiful.

During my time at Skowhegan, being in this really beautiful rural setting, it's so meditative and peaceful, I found myself walking around with my camera and thinking: what am I going to do today? I'm just going to look at the rocks and the trees. I kind of hit a wall with how I was depicting environments in my work over the last couple of years. I hesitate to use the word landscape because that to me has a more grand connotation. I think it has something to do with the specificity of "this is a place" on a kind of grand level. Like David Sherry's work. He's photographing at these monuments and it is very much about this is this specific Sacred Space or it's this space that's under threat. I'm not as invested in that. For me it's more about the quieter moments or the quieter discoveries.

I was walking around thinking how can I use the environment and the landscape to make drawings essentially? From that very simple exercise I allowed things to expand and contract and become more complicated. I was also focused on making portraits, as opposed to pictures with people in them. In other words, getting after something that's more about a direct engagement with a person. Maybe revealing something about that person, which is a complicated problem. So just being in the lake at Skowhegan, and being around the trees and basking in the sunlight, I was realizing we're so connected to these sorts of natural systems even though we live in New York City and we're in a lot of ways super detached from nature. But when you get into those spaces, it's fascinating how immediately we connect back to these systems. Laying by the lake for a day, I was like, oh my God, I feel so relaxed and nourished! So in the same way I was trying to connect to portraiture I was trying to figure out what this connection to the environment was about.

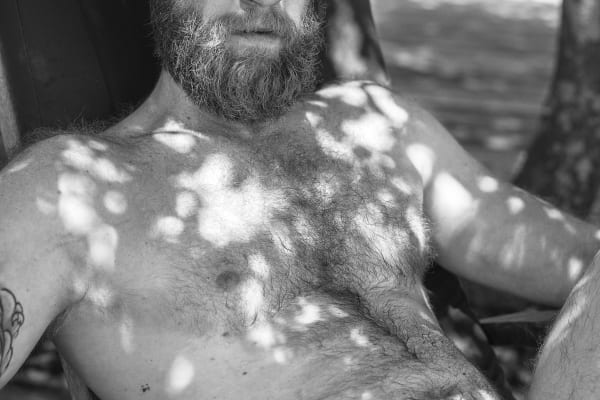

I was thinking a photograph like this (Zack in Dappled Light (Fire Island)) all of a sudden becomes, as you say, part of nature, whereas, something in a studio pulls you out of nature. That constructs and removes us from the natural into a kind of system of semiotics, of meanings, that detach themselves from life. This is a body that looks like it's living by the lake. What I love about what you're saying is that it's not only that the body itself becomes more natural, and it's not a body that's chosen for is kind of ideal properties, but all of a sudden when we look at a photograph of nature instead of thinking "Isn't that beautiful," it pulls the nature photography that you're making into that same space, right out of the remove of the impossible ideal. You know, this body sits in the same space as the tree you photographed. I don't know if you were calling them portraits, but on some level they do blend. They come together on some beautiful level and maybe that is through black and white, through lighting, through the space that you choose to place the model or choose the tree or whatever you're photographing. There is this sense of overlap, that they meld in some way.

Untitled/Trees and Light (Skowhegan), 2019

The lighting is always one of the things I think about the most when making work whether I'm using natural light or flash. In this sequence of photos, there's the trees with the dappled light coming through them (Untitled/Tree and Light (Skowhegan)). There's the portrait of Zack with the light all over his body and then the picture of the lake where the light turns the water into this almost metallic surface (Untitled/Lake Water (Skowhegan)). When I first put those three photos next to each other, I loved how the light felt like it was moving through the three photos and transforming depending on what surface it was on, and that was really exciting to me. Also the way that I use light and shadow is a way to create more exciting compositions. I get a lot of questions about light but I think about shadows as equally important.

I guess this is still something I'm struggling to figure out or comprehend, but like you were talking about, we all shit and cum and bleed. We have these systems in a similar way that plant life or animal life or water all have. There's these cyclical or systemic things that happen and I'm attempting to draw parallels between the blood that runs through our veins and the water that runs through a tree and gives it life.

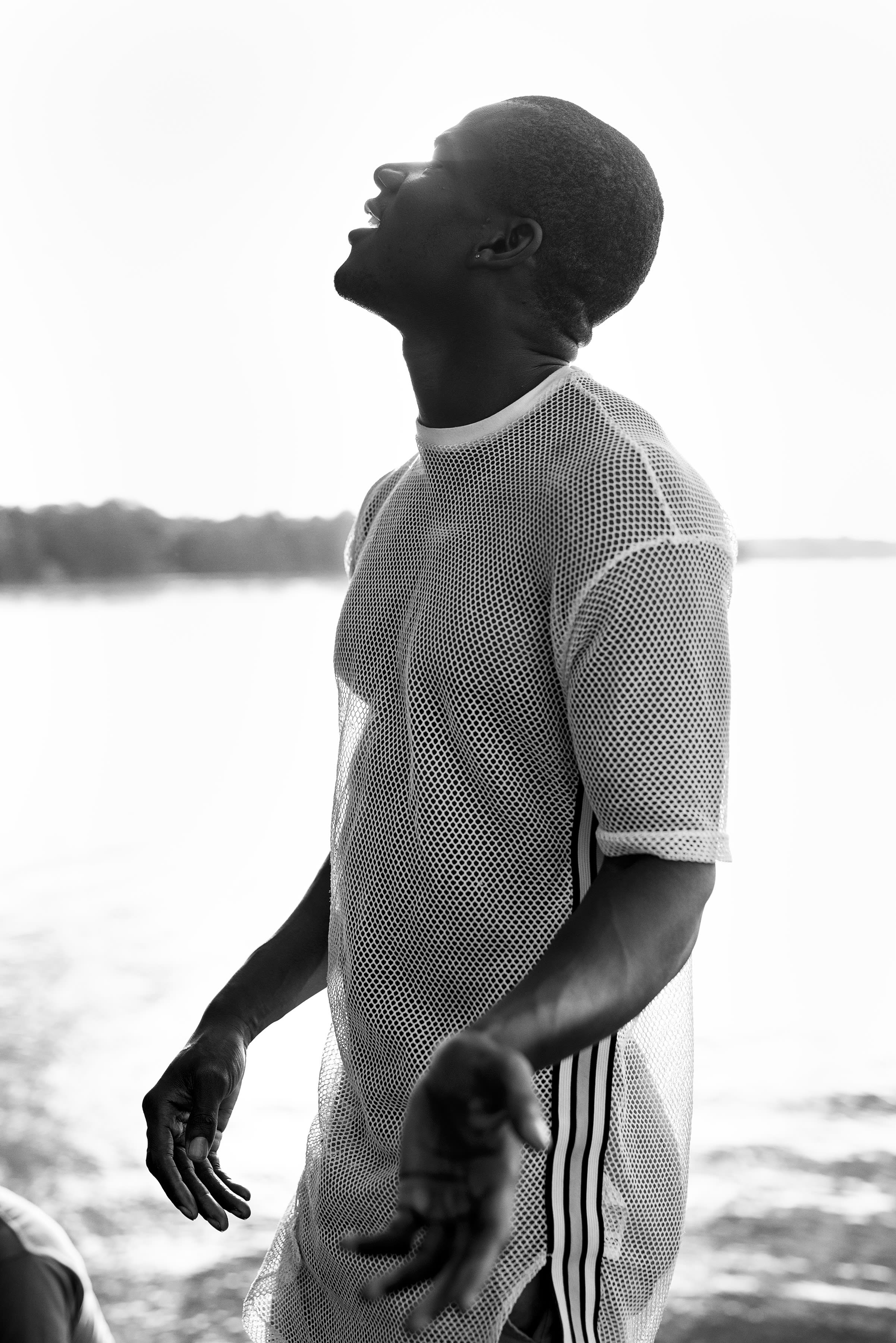

I'm trying to expand a little bit beyond photographing just gay identified men, and it was funny when I was at Skowhegan I said, "I'm going to photograph straight people." Which I did, but the pictures that I ended up with that are the most successful are all of queer people. So take that for what it's worth. Right now there is this conservative movement to continue to repress queer people, and there's this movement to ignore the fact that we're destroying our planet and that it's incredibly fragile right now. So I think there's also a connection between the incredible beauty and strength the planet holds and that queer people hold and historically have been able to maintain despite whatever sort of nonsense was happening around them. So I feel there is a kind of connection there that I'm trying to bring out.

I think my work is optimistic. It shows for the most part positivity and strength, but I also love photographs where you see people's scars. Prior to Skowhegan, I photographed my friend Eddie in his tub after he had surgery on his leg. He's all bandaged up but he's got this big grin on his face. I photographed my friend Hunter Reynolds after he had cancer removed from his nose and needed a skin graft. In order for the skin graft to heal he had this crazy, like, skin tube connecting his forehead to his nose, and he really wanted to be photographed in that state. It's the history of our individual bodies, and there is this idea that we can be battered but not beaten.

I love how you explain this better than where I was going to go, but I'm going to go there because I think that on some level it explains your optimism. The beauty of the body, even if it's scarred, makes me think of the photographs from the 80s and 90s, or the ones that documented Hujar's own death, or of these emaciated bodies. Having taken care of a partner who died of a brain tumor pulled me into the body and made me no longer afraid of shit, piss, or touching a body that's slowly slipping away. It pulled me back into nature and an understanding of cycles of life, or how we are connected to nature and how, when we're living and we're feeling most energized, we try to separate ourselves as if we're superhuman or we're not part of nature. And so I think there's something beautiful about what you're saying, that it keeps a life in that body, even if it's scarred. Whereas in some of the AIDS photographs, it looks like life is being drained out of that body and there's an incredible sadness, instead of this kind of beauty and optimism and joy. Joy is a word I'd use to describe the light in your pictures, the way it lands upon the body, even if it is scarred.

In continuing the research that I started in grad school, reading stuff that was being written, or looking at work that was being made in the 80s and the 90s, even if it was directly confronting this unbelievable tragedy there was joy, there was strength and you could see it in the resistance, the activism that was happening then. I always found that really inspiring. Actually reading George's (Chauncey) book[1], disproved this idea that queer people were just totally hidden, totally scared, didn't have any form of community, didn't have a way to express themselves or celebrate. And it's really amazing and inspiring to see how they found all these ways to circumvent the discrimination and the repression and create these really beautiful communities of all types. I think that history continues to this day.

Jordan Smoking in Mesh Dress (Skowhegan), 2019

I love how you connect that to the planet too. I mean, I want to have the hope that the planet can survive how horrible we are being to it right now, that it has that kind of resilience. But I love the metaphoric connection of queer community that kind of survives and finds some way to survive under incredible repression. The planet itself will outlive us, it will outlive this generation whatever state it's in, you know, whatever poison we put in it.

Yeah, we might not last as long as the planet! I always want to make beautiful photographs. I want people to be drawn into the surface of the photograph and then have an unfolding experience that is hopefully more complicated than just like, "oh, wow, this is really gorgeous to look at."

I feel so much anxiety about the state of the planet right now, especially with the fires in Australia. And the thing that actually makes the anxiety worse is the fact that the people in power continue to lie, and deny, and they just don't give a fuck. That's terrifying and I don't know how to deal. Maybe it's a small way to soothe myself by making these photos.

I got to go to Iceland in September after Skowhegan and it was somewhere I've always wanted to go. It's an insanely beautiful part of the world. And I would go between just being in complete awe of everything and then having these moments where my stomach would drop and be like, this is all going to be changed. My friend and I did a glacier hike and the guide was telling us that this big lake at the bottom of the mountain wasn't always there. It didn't used to be a lake, It was all ice as of ten years ago. It just made me want to lay down and give up.

Beach Erosion (Fire Island), 2019

There is this sense that we're all under threat if we just continue to let the planet be destroyed like this. But again, it is relating that threat that queer people live with daily, and the threat to our planet. There's a photo of Fire Island (Beach Erosion (Fire Island)), of the sand and the shadow and the footprint, that little cliff that you see is just beach erosion. I started going to Fire Island a little over a decade ago. I've been in the city since 2005 and I think the first time I went was maybe in 2007 or 2008. The beach has changed dramatically in those years, you know, we've seen it getting washed away. There's a sense that this place that holds so much history, and beauty, and natural splendor might be underwater soon, just totally gone and what that means for our community is one thing but what that means for our planet is another thing.

When you talk about beauty you mean a different concept of beauty and again, I'll go back to Mapplethorpe. Your work shows a more natural beauty and I sort of love that about them. I can live in that space. Whereas with Mapplethorpe I feel more voyeuristic at what I'm looking at. I feel detached. I'm studying something instead of being part of it or in the kind of enjoyment I feel towards whatever is happening in your photographs.

A lot of times when I talk about beauty in my photographs I do think more in terms of a beautiful photographic object and then sort of after that it becomes more about the beauty that I see in the subject or whatever it is I'm photographing. I mean, it sounds kind of cliché and corny to say this but I do think that everyone has beauty. There's so many different types of bodies and again, getting back to this idea of the history that we carry on our bodies through scars, or tattoos, or our size and shape. All those things give a richness to their personhood when they're photographed.

Elle/Truck (Skowhegan), 2019

Not to get too much into the politics of representations of bodies and beauty standards, but when I when I first moved the city in 2005, I was 23, and I kind of remember feeling weird about being attracted to certain types of guys that didn't fit into the standard of the bodies you see in porn or the bodies you see in movies and magazines. Like heavy guys, older guys, or really skinny guys. Eventually I realized I was sort of repressing my own desires and attractions because I was worried about what some imaginary other person would think. I mean, I don't want to paint this picture that that doesn't exist amongst gay men. I think there's a lot we could talk about there, but I have found in New York that there is a sort of acceptance for all types of people. You brought up aging and I have found, myself, and particularly with other gay men around my age, I'm 37, are really attracted to older guys. I think part of it is because we grew up without a lot of mentors or father figures and also this knowledge that all these men who could have been our teachers, our friends, our lovers are gone. Really up until I turned 30 I didn't have a lot of that guidance or gain a lot of that knowledge that you gain from older generations and there is an attraction in that.

It's not always about sexual attraction. One of the things that I've been thinking about in the work that I made, in particular at Skowhegan and since then, is that so much of my earlier work was focused on sexual desire or sexual engagement, but now I'm curious to see what other types of desire and sensuality I can show in my work that's not necessarily tied to sex. Since I've been back from Skowhegan and I have a studio, It seems like the studio space has kind of a sexually charged atmosphere and I'm interested in getting back to that way of thinking and working. And it's kind of fun to be exploring that in tandem with this other exploration I really dove into this summer. We'll see where it all leads.