Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) played a pioneering role of the greatest significance in the development of printmaking in the United States. Originally founded by Tatyana Grosman in 1955 as a way to generate extra income, reproductions of paintings created there came to the attention of William Lieberman, who at the time was a curator at the Museum of Modern Art. Impressed by their quality, he encouraged Grosman to create original prints through collaboration with artists. She decided to follow his advice and sought out young artists she knew of, who in turn brought more artists intrigued by the output. ULAE ultimately became a crucial site for the creation of prints by leading artists of the day and was responsible for incredible advances in the medium, a tradition it continues to this day.

Larissa Goldston, the current co-owner and director of ULAE, grew up observing changes in the landscape of printmaking firsthand. In light of our viewing room From Paris to New York: Transformations in Printmaking, we were honored to speak with her about her experiences. In this conversation with art historian Jennifer Earthman, Larissa provides her perspective on the history of printmaking in general in both Paris and the United States, ULAE’s crucial role in the development of printmaking in America specifically, the unique experiences of women artists in comparison to their male counterparts, and stories of collaborations between artists and printmakers, ultimately providing a lens into a unique time in the history of printmaking.

View of the drying rack after printing one screen for Sarah Sze’s print White Flash, 2020. Image courtesy of Universal Limited Art Editions.

The viewing room From Paris to New York: Transformations in Printmaking is concerned with prints as autonomous, original works of art. What would you say are the principal driving forces that caused artists to realize the true capabilities of prints beyond as a means of reproduction?

The artists of the 1950s and '60s were trailblazers. They were curious, ambitious, and wanted to use every medium possible to make work. I don’t think any of them came hoping to reproduce a painting; they came hoping to expand their knowledge. I don’t think any of the artists that started at ULAE understood the significance of what they were doing right away. Most of them were intrigued by the medium and by the idea that their work could be seen in multiple homes or institutions. And then some of them, like Jasper [Johns], were captivated by the idea that they could revisit an image over and over again, always changing it.

What do you view as the most significant political and cultural events which impacted printmaking in the 20th and 21st centuries?

There are several key moments. The first one is the Great Depression: The WPA (Work’s Progress Administration) was established and set up graphic studios to help unemployed artists. The AAA (Associated American Artists) was also established in 1934 to help stimulate the art market by inviting artists to make limited edition prints to be sold. The second one is the Space Flight and Lunar Landing in 1969: many artists made prints about the space program. Lastly, we have the war in Vietnam and later the AIDS crisis. The protests against the Vietnam War had a huge impact in the mid 1960s-1970s. Posters were used to educate and persuade people into believing the atrocities of the war. In the 1980s, printmaking played an important role in the AIDS crisis using reproduction to induce change. Posters fed the first wave of activism (Silence = Death made by ACT UP[1] being the most significant) but as the crisis raged on, artists used their work to deal with grief, anger, sex, illness, anxiety, fear, and ultimately the death that ravaged the gay community.

On a related note, what effect do you think the invention of photography had on printmaking?

In short, the history of lithography can be outlined in four steps–the creation of the process, the invention of photography, the offset press, and the invention of the litho plate. In the early days of photography, printmaking worked in tandem with it, aiding publishers with photo illustrations in books, newspapers, and magazines. As time moved on, printmaking helped broaden photography’s possibilities and some artists began to realize its potential in providing them a whole new realm of techniques. No one did this more significantly than Robert Rauschenberg (although Warhol might come a close second). I can’t think of a print that Rauschenberg made without incorporating photography, starting with his very first print made at ULAE in 1962 and ending with his last in 2007.

Printmaking was not viewed as a true fine art in America for decades after it was in Europe. It was not even taught at universities until 1922. What do you believe is the reason for this?

America has always been behind Europe in appreciating and accepting the arts. On top of that, printmaking was generally associated with newspapers, magazines, and posters in America. It was considered a trade, not a form of fine art.

Print workshops consist of master printers and countless employees all helping and transmitting knowledge to one artist. How do collaborations take place, and how does this collaboration alter the idea of art created in solitude?

Any artist that has truly embraced printmaking will tell you that their experience in the printmaking studio has altered and/or advanced the work they are producing in their own studio. Printmaking is about layering and that layering is very different than the layering that occurs in a painter’s studio. In their personal studio, a painter makes a mark and that mark is immediate and it is theirs. In the printmaking studio, when a mark is made, it is not only the artist’s mark but also that of their collaborator. That mark has to be processed, inked, and then printed before they can even see it. It is a slow and tedious process and it is not for everyone. It requires patience, persistence, and dedication to learn all of the various processes. That being said, when someone embraces the possibilities that printmaking has to offer them, the collaboration between artists and printers can be extremely fulfilling.

How do you think print workshops compared in Paris and the United States in the 20th century?

There is no doubt that the Paris printmaking shops set a tone for the shops that would follow in America. Paris was the beginning of the printmaking revival and the acceptance of etching as an autonomous art form. Atelier 17, started in 1927 by Stanley William Hayter, was the renowned studio in Paris until the war and early on published editions with Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró, Wassily Kandinsky, David Smith, and Yves Tanguy. During the war, Hayter moved his studio to New York and solidified his place as a printmaking pioneer working with artist like Louise Bourgeois, Alexander Calder, Marc Chagall, Salvador Dali, Willem De Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Louise Nevelson, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko.

Unlike Paris, the print revival in America was started by women, not men. Tatyana (Tanya) Grosman started ULAE in 1955 with no technical experience. She had intended to make limited edition books in the tradition of livre d’artiste for income. The evolution of making limited edition prints was by chance and the success of the studio was driven by sheer necessity to make a living and create beautiful objects, but it ultimately set the tone for other print workshops. Grosman was followed by June Wayne, the founder of Tamarind Institute[2], who founded it to save lithography. Wayne wanted to “create a pool of master-artisan printers in the United States” while also hoping to create an intimate collaborative setting for artists and printers to work together. Only two years later, Crown Point Press was started by Kathan Brown. It wasn’t until 1965 that men entered the game when Ken Tyler, an alumnus of the Tamarind Institute, started Gemini and was joined quickly by Stanley Grinstein and Sidney Felsen.

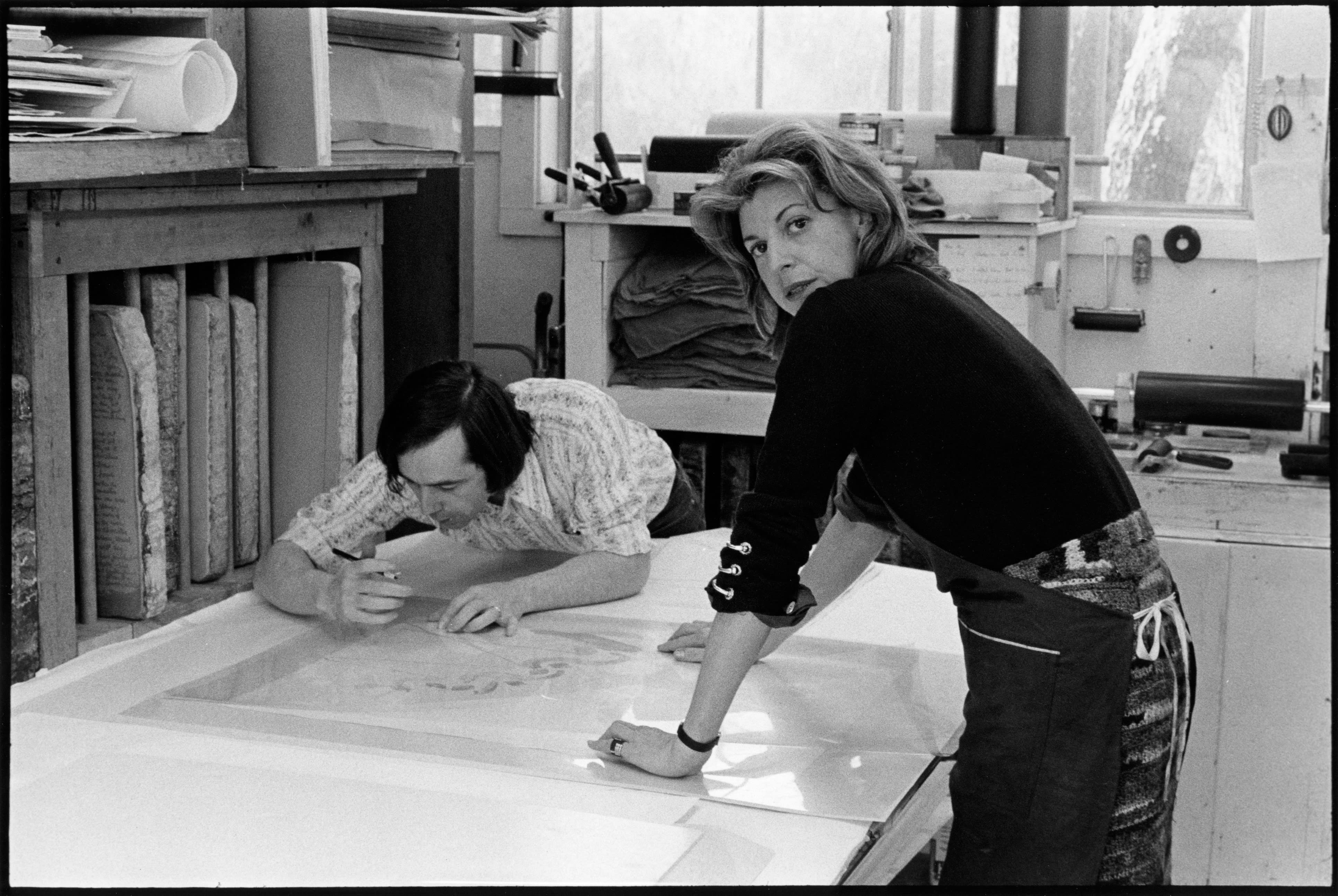

Bill Goldston and Helen Frankenthaler collaborating in the studio working on her print “Venice II.” West Islip, NY, 1972. Photo by Edward Oleksak / Courtesy Universal Limited Art Editions.

For ULAE, as a workshop, what has been the guiding principle to work with one artist or another in such a way that when looking at their editions today, one can see the development of the history of art over the past half century?

I don’t think there is a guiding principle, I think there is only allowing the artist the freedom to make an image and providing them the technical assistance needed to help them realize it. At ULAE, there are no restraints put on artists. Artists can work as long as they want on an image. We have often heard people say that artists don’t come to ULAE to make prints, they come to make projects. We embrace that thought. We never shy away from a challenge. In the beginning of printmaking in America everything was new and essentially an experiment. Now, the younger artists have decades of work to reference and the printers have decades of experience to build upon. If you look at some of the newer artists working at ULAE you can easily see the influences of artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg on their work.

What led ULAE founder Tatyana Grosman to invite Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg to the studio? Did she hope they could help inspire other artists to try out printmaking?

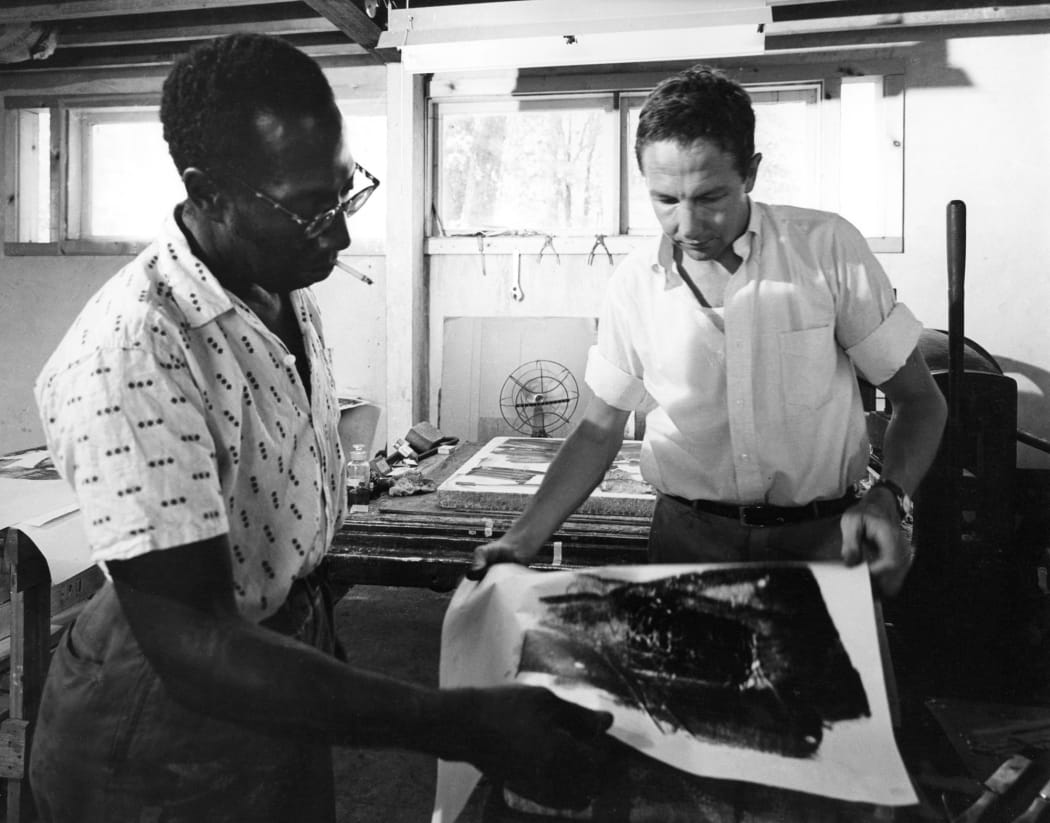

The first artist that Tanya invited to work at the studio was Larry Rivers. When she eventually started ULAE, she had intended to publish livres d’artiste, books with poems and illustrations, with the idea of Larry Rivers doing illustrations and Frank O’Hara writing the poems. Frank wasn’t able to work as much as Larry, so Larry started drawing on stones and made single images. Those became the first editions that ULAE published and started Tanya on the road of limited-edition prints. Larry was friends with many young artists, such as Helen Frankenthaler (who was married to Robert Motherwell), Grace Hartigan, Lee Bontecou and Marisol Escobar. He encouraged many to make prints with Tanya. Tanya saw Jasper Johns’ show at Leo Castelli and pursued him for two years before he committed to coming. Then, she met Robert Rauschenberg while delivering stones to Jasper. Following their arrival, it was a domino effect. They brought Ed Schlossberg (who brought Buckminster Fuller), Cy Twombly, James Rosenquist, and Jim Dine.

ULAE is well-known for working with Helen Frankenthaler on woodcuts, one of which is included in this viewing room. What led to the embrace of such an old medium and how do you think ULAE helped revive it?

This is such a fun story. Bill [Goldston] had just finished printing I Need Yellow and Tanya asked if Bill had any messages for Helen. He said, “Tell her I want to make a woodcut.” He had been thinking about how to use the letter press and thought that printing woodblocks on it might be interesting. Helen called Bill from her studio when Tanya relayed the message to say how excited she was about the idea. When she came to the studio next, she drew on the blocks and tried following the line with the saw. It was a disaster–she was breaking the saw blades and ruining the saw and all the while cursing. She made everyone leave the studio except Bill. Finally, he said, “just draw with the saw and don’t try to follow the line.” So that is what she did and that is how East and Beyond was made. They proofed and printed it all in one day. Then they started Savage Breeze and the print took nearly a year and a half to finish. They had a hard time getting the right effect until they found this crazy paper from Nepal and Helen was so thrilled with it that she also made Vineyard Storm and printed it on the same paper. Trial Premonition followed. Those prints got Helen going on the woodcut medium.

How have other women artists embraced printmaking? Could printmaking and its related spaces be viewed as providing them with a sense of freedom and empowerment as their careers were downplayed by institutions, major collectors, and their male counterparts?

My observation has been that women work differently in the studio than men. It is fascinating to watch. Men are much more controlled about how many plates they use, how much of the printer’s energy will be exhausted processing and printing the plates and how difficult the project will be to realize. Women seem much freer about using however many plates it takes to realize their vision. For example, Jasper Johns has never used more than 11 plates to realize any image and Elizabeth Murray once used 143 plates and 20 colors and 14 sheets of paper to create a 3-dimensional print (Shack, 1994) that took ULAE years to edition.

Elizabeth Murray. Bill Alley, 2006. Three dimensional lithographic construction in 28 colors on Arches Cover paper, 35 x 41 1/4 x 1 1/8 in. (88.9 x 104.78 x 2.86 cm). Edition of 25. Image courtesy of Universal Limited Art Editions.

The printmaking studio space empowered women. It was a place they were treated as equals to their male counterparts. Tanya didn’t choose to work with artists because they were men or women, she simply wanted to work with people who made beautiful objects. At first it was a coincidence that ULAE kept a constant roster of men and women in nearly equal numbers working in the studio but as the years went by, it became intentional. In the early days, being associated with studios like ULAE, Crown Point Press, and Gemini likely gave collectors, galleries, and museums confidence to collect the work of women artists. There is still a long way to go to equality but we seem to be heading in the right direction.

Lastly, ULAE is renowned for expanding into many other different kinds of printmaking as well, such as aquatint, etching, lithography, photolithography, and silkscreen, to name a few. How do you see the workshop adapting to and going into the future in light of the digital age?

ULAE has always been at the forefront of technological advances in printmaking. When digital printing became more prevalent in 1999 we began doing research into ways to use the medium as a form of printmaking rather than a reproduction device. We worked with both paper producers and ink producers to understand the medium in depth: its possibilities and its limitations. We purchased a Phase 1 digital camera (which had a digital scanning back), which opened up a whole new set of possibilities. As soon as we were able, we purchased a large-scale digital printer and began experimenting with the equipment so that we would be able to teach artists how to work successfully with the medium. We published our first print using the digital printer in 2000 with Carroll Dunham. After that, Jane Hammond had an idea to photograph herself with the Phase 1 camera and then place tattoos all over her body. We collaborated with a paper making company in Japan in order to develop a handmade paper that could handle the ink. A couple of years ago, Lisa Yuskavage was having a hard time figuring out how to create the rich color in printmaking that was so prevalent in her paintings. She and my father worked closely for months on a group of images in order to accomplish this feat. Most recently, we worked with Sarah Sze on a project that incorporated digital printmaking with lithography, silk-screen, watercolor and collage. Digital printmaking has proven to be a marvelous tool thus far, and we look forward to further advancements in the future.

[1] ACT UP is the acronym for the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, an activist organization working to end AIDS.

[2] The Tamarind Institute is a non-profit workshop devoted to lithography, originally founded in Los Angeles. Today it is a part of the University of New Mexico.