A leading scholar on the work of Sol LeWitt (1928-2007), art historian David S. Areford has delved into the artist's extensive body of work through two recent groundbreaking publications shedding light onto LeWitt's intricate relationship with art history and his innovative contributions to the traditions of printmaking, photography, sculpture, and painting. He is currently at work on a third book on LeWitt, a monographic study devoted to his wall drawings and gouaches. In this conversation with Lora Milutinovic, Areford offers his unique insights into LeWitt's artistic process, highlighting the artist's streamlined methodology and ability to engage with the technological advancements and cultural currents of his time. For instance, Areford discusses LeWitt's gouaches, explaining the peculiar choice of this often disregarded and marginalized medium, and how these artworks were made only by the artist's hand as opposed to the teamwork involved in the material execution of his wall drawings. Professor Areford's insights are an invitation to critically engage with the enduring legacy of one the most influential American artists of the twentieth century and to consider his works through a constant dialogue with art history.

David S. Areford in the studio of Sol LeWitt in Chester, Connecticut. Photograph by Jody Dole, image courtesy of the author.

Welcome to Zeit Contemporary Art, David! It is truly a pleasure to speak with you about the career of Sol LeWitt, and I am very curious to hear your insights as a leading LeWitt scholar. When reading your work, I was especially intrigued by your training as an expert on late-medieval European devotional art. How did you start exploring the artwork of Sol LeWitt?

I've always been interested in contemporary art, which was my secondary area of study during my early graduate school years. But yes, I was trained primarily as a medievalist, specializing in the fifteenth-century art of northern Europe. Some of my publications have explored illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings, but my first book focused on devotional woodcuts and their various functions. Thus, many know me mainly as a historian of early printmaking. I became interested in the art of Sol LeWitt in 2008, with the opening of a spectacular retrospective of his wall drawings at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams, which has recently been extended until 2043. Since it opened, I've visited this show at least once and sometimes twice a year. I quickly became aware that LeWitt worked in multiple mediums, including printmaking, which was the focus of so much of my early scholarship. And thus, it was his wall drawings and especially his printmaking that provided my initial path into his conceptual art.

As you've mentioned in your publications on LeWitt, there are interesting connections between his work and fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italian art. Was this surprising to you?

As I began my research for Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints, it became very apparent the degree to which he was engaged with art history. Indeed, he often talked about his admiration for early Renaissance Florentine architecture, as well as fresco paintings by Giotto, Filippo Lippi, and Piero della Francesca. And, in various ways, these artworks had an impact on his printmaking, as well as the visual language of his art overall, especially as reflected in the wall drawings. This influence became more pronounced after he moved to Spoleto, Italy in 1980. In my new book-in-progress, I delve into this more deeply, trying to figure out the many ways in which LeWitt's work - especially the wall drawings and gouaches - is in dialogue with the history of painting.

Another surprise for me has been discovering LeWitt's willingness to engage quite explicitly with the historical past, as well as his personal and religious identity. For Locating Sol LeWitt, I wrote an essay that explores six site-specific works he made from 1987 to 2005, each responding to specific Jewish contexts in the United States and Europe. The last of these was a sound-and-sculpture installation in a former synagogue in Germany.

When reading Strict Beauty, I appreciated the clear way you organized the discussion of so many different prints made over the course of LeWitt's career. How did you decide on the organization of the book?

Partly the book is organized around different visual languages, from lines to geometry. These languages were often used simultaneously, but it was useful to create a loose chronological narrative based on when each vocabulary was introduced. His work increased in complexity as he added new ways of expressing his ideas, but he always saw his art and ideas as straightforward. In some early interviews, he was quick to dispel the notion that his art was difficult to understand.

Sol LeWitt's gouaches on paper Squiggly Brushstrokes, 1997, and Irregular Grid, from 1999. Private collection, New York. Image courtesy of Zeit Contemporary Art, New York.

As an artist, it seems that LeWitt was focused on simplicity as the most efficient vessel for the idea. In Strict Beauty, it was interesting to learn of the systematic way he would explore the potential of a fixed set of lines or colors through different combinations and permutations. How do you view his approach to creativity within such artistic constraints?

For him, it was a highly productive way of working. Of course, he wasn't alone in this way of thinking, especially among his generation of artists, particularly American artists seeking a way forward in the wake of Abstract Expressionism. Instead of tapping into his emotions, psychology, or personal worldview and translating that onto a canvas, he wanted to distance himself from the final artwork as much as possible. By generating his work through predetermined ideas, systems, and procedures, he could set the work in motion so that it had a life of its own. He increased the distance by eventually hiring others to install the wall drawings and to make the structures, as well as working with master printers who could simply follow his directions. So, for LeWitt, his systematic approach was very productive and solved the problem of constantly making decisions, which he saw as interfering with what should be a clear idea. Interestingly, later in his career he freed himself from some of his self-imposed rules. He introduced new seemingly expressive visual languages - wavy, curvy, loopy doopy bands and brushstrokes - full of energy and movement. But as I argue in Strict Beauty, there is always a level of restraint or control.

In terms of the development of LeWitt's visual language, it is interesting to see the way in which he moves from simple lines to geometric forms which gain volume, movement, and a sense of three dimensionality. Again, one is reminded of Renaissance frescoes and how they depicted space.

Of course, flatness and depth were very current topics among artists - especially painters - when LeWitt arrived in New York City in the mid-1950s. He initially saw himself as a painter and was very much invested in exploring different modes of painting, from still life and figuration to abstraction. Eventually, when he began working on the wall drawings, he was initially interested in asserting the flat surface of the wall. Later, he introduced layers of color ink washes and began exploring an illusion of depth. But he wanted that depth to be as shallow as possible. He didn't want the wall to become a window to another world, but to remain present on some level. This effect is part of what he appreciated about Giotto and other fourteenth-century fresco painters who had not completely figured out perspectival and naturalistic space. LeWitt's art was one of linear and geometric abstraction. And he tended to use the most basic isometric projection to suggest three dimensionality and depth. After his move to Spoleto, LeWitt regularly visited the great late medieval and early Renaissance frescoes in Assisi, Arezzo, Orvieto, Padua, and Florence. But he was also interested in ancient Roman wall painting in Pompeii (especially the Villa of the Mysteries) and in the museums in Naples and Rome. As I work on my new book, it is clear to me that all these frescoes had a profound impact on his wall drawings - from their visual effects and scale to their site-specificity and engagement with their architectural settings.

Your new book project also explores LeWitt's gouaches. With this medium, LeWitt could not completely distance himself. He had to make lots of choices and deal with the limits of his physical body and his working space. How can we understand the gouaches in relation to his wall drawings?

Most people are surprised by LeWitt's gouaches, even though he made thousands of them and regularly exhibited them in galleries around the world…

Yes, the visitors at our recent presentation at the Salon du dessin in Paris, France, were surprised by the gouaches we were displaying, seeing them as the opposite of what they already know of LeWitt's art. More than one person said in awe and wonder: "They're so jazzy!"

Sol LeWitt. Irregular Form, 1999. Gouache on paper, 7 1/2 x 14 7/8 in (19.1 x 37.8 cm). Private collection. Image courtesy of Zeit Contemporary Art, New York.

That reaction seems partly about his painterly use of the medium but also about his seemingly improvisational visual languages - the irregular forms and irregular grids, the tangled bands, the horizontal, wavy, and squiggly brushstrokes - which are quite different from the wall drawings. Unlike the wall drawings, which can be installed by others, the gouaches can only be done by LeWitt. They are personal and signature works, dependent on his individual hand, his touch. They are the products of his almost daily practice of painting in his studio. And they range dramatically in size, from seven by eleven inches to five by fifteen feet. He spoke about the pleasures of making them, the motion of his arm and body. But he stressed that it was a "controlled movement" and not one that expresses emotion. Thus they still conform to certain rules. But they also amplify an important aspect of his art overall - his willingness to leave room for accidents and unforeseen effects of color and form. Audiences and critics have struggled to figure out how these works make sense in relation to what they know about LeWitt's rule-based conceptual art.

At the beginning of his career, critics and art historians were mainly interested in how LeWitt was expanding the parameters of drawing. But now that we have a full retrospective view of his career, I'm more interested in the many ways he was transforming the possibilities for painting. For an artist who had stopped painting in the mid-1960s, the gouaches were a way for him to return to the medium and all the aspects of abstraction he had rejected - issues of the brushstroke and mark-making, layering, transparency, and opacity, etc.

Hearing you talk about these aspects of his painting makes me wonder about his specific choice of gouache. Why did he decide to work in gouache?

This is an important question for my project. When he returned to painting in earnest in the 1990s, why did he not take up oil painting again and work on stretched canvas at the easel? Why decide to paint in gouache on sheets of paper? I think his decision was partly based on the somewhat marginal status of gouache in art history. Gouache is very similar to watercolor, but the pigments are denser and typically opaque. It is usually thought of as a medium for working out ideas, for creating "studies" before completing a larger work. Also, gouache and its paper supports are quite fragile and susceptible to damage. Again, I think this is ultimately another method of distancing himself (as we were discussing earlier). He intentionally chose to work with a medium that's not quite fully "painting," because it allows him some distance from painting's standard history (whether that's about fresco painting or oil painting). This is also the reason for his use of the term "structures" for his sculptures and "wall drawings" for his mural works (even when they became completely painted). It was a way to assert an independence from those traditional art historical categories and narratives.

Earlier you mentioned that the visual languages of the gouaches seem intuitive yet follow rules, like any language. Can you elaborate on these rules?

Early in his career, LeWitt used the word "grammar" to describe his modular and serial use of visual motifs. Thus, with the gouaches, there is kind of grammar to each language. Overall, many share the same characteristics, such as being "all-over" in their design, covering the paper sheet edge-to-edge and thus defeating any clear compositional focus. But each is consistent in terms of the specific visual vocabulary - the width or length of the marks, their particular trajectories, their distinctive character (straight, horizontal, curvy, squiggly, etc.). With that said, sometimes within the parameters of a language - "irregular grids," for example - LeWitt allowed a variation to emerge, as if he were speaking in a different accent or even with a different emotional tonality.

And when one is viewing these works in person, it almost seems like having a conversation. After extended looking, the autonomous logic of the language becomes clearer. Thank you so much for our conversation. It was fascinating. I'm looking forward to your next publication on the art of Sol LeWitt!

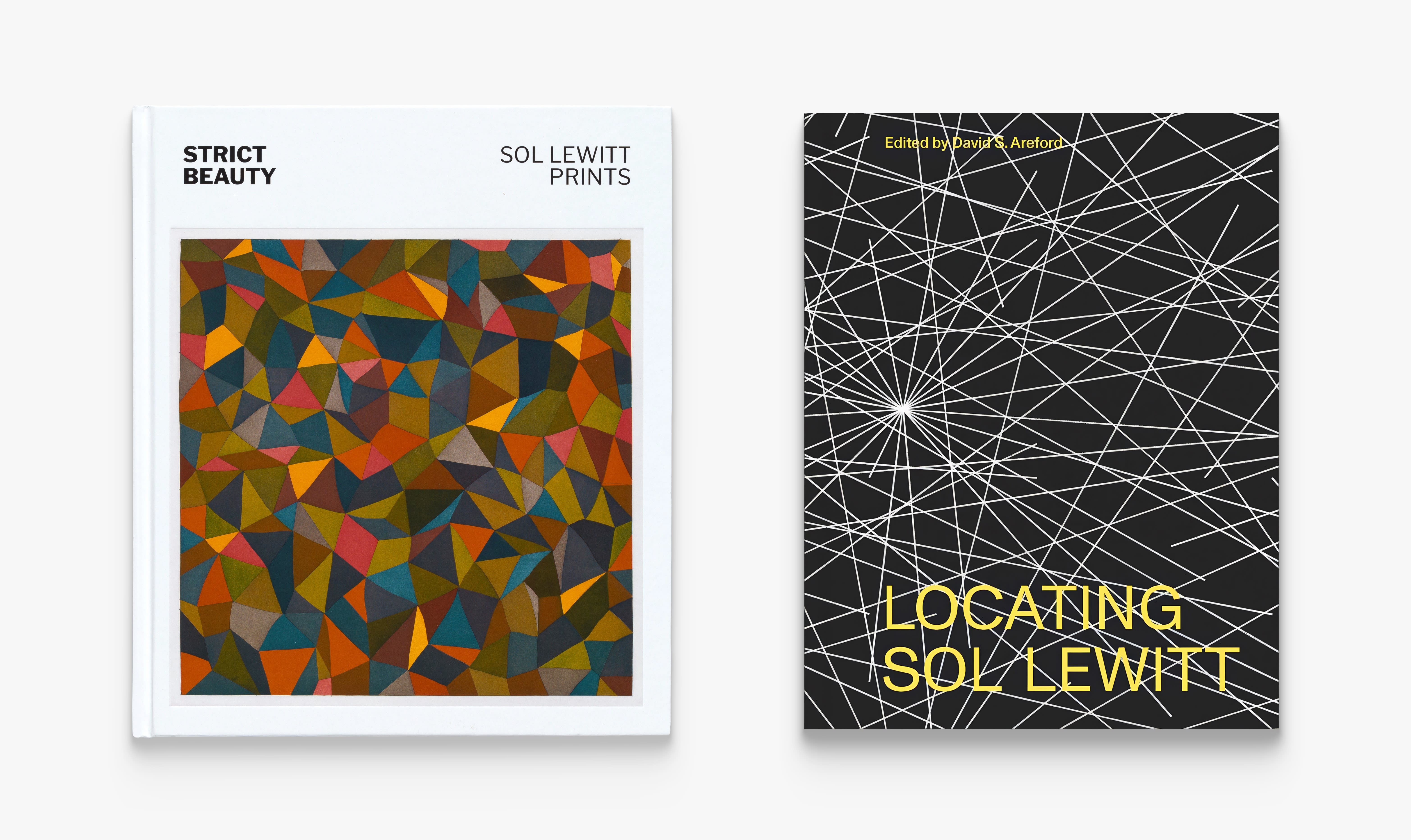

David S. Areford's Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints (2020) and Locating Sol LeWitt (2021), both published by Yale University Press, New Haven & London.

_________________________________________

David S. Areford is Professor of Art History at the University of Massachusetts Boston. He is the author of The Viewer and the Printed Image in Late Medieval Europe (2010), The Art of Empathy: The Mother of Sorrows in Northern Renaissance Art and Devotion (2013), La nave e lo scheletro: Le stampe di Jacopo Rubieri alla Biblioteca Classense di Ravenna (2017), and most recently, Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints (2020). He is also editor of Locating Sol LeWitt (2021), featuring essays by eight scholars exploring the full range of LeWitt's art. Professor Areford is currently at work on a new LeWitt project, a book tentatively titled Sol LeWitt: To and From Painting.